Theory: Threading

We’re going to be using coroutines as our threading solution. Let’s see how exactly that’s done.

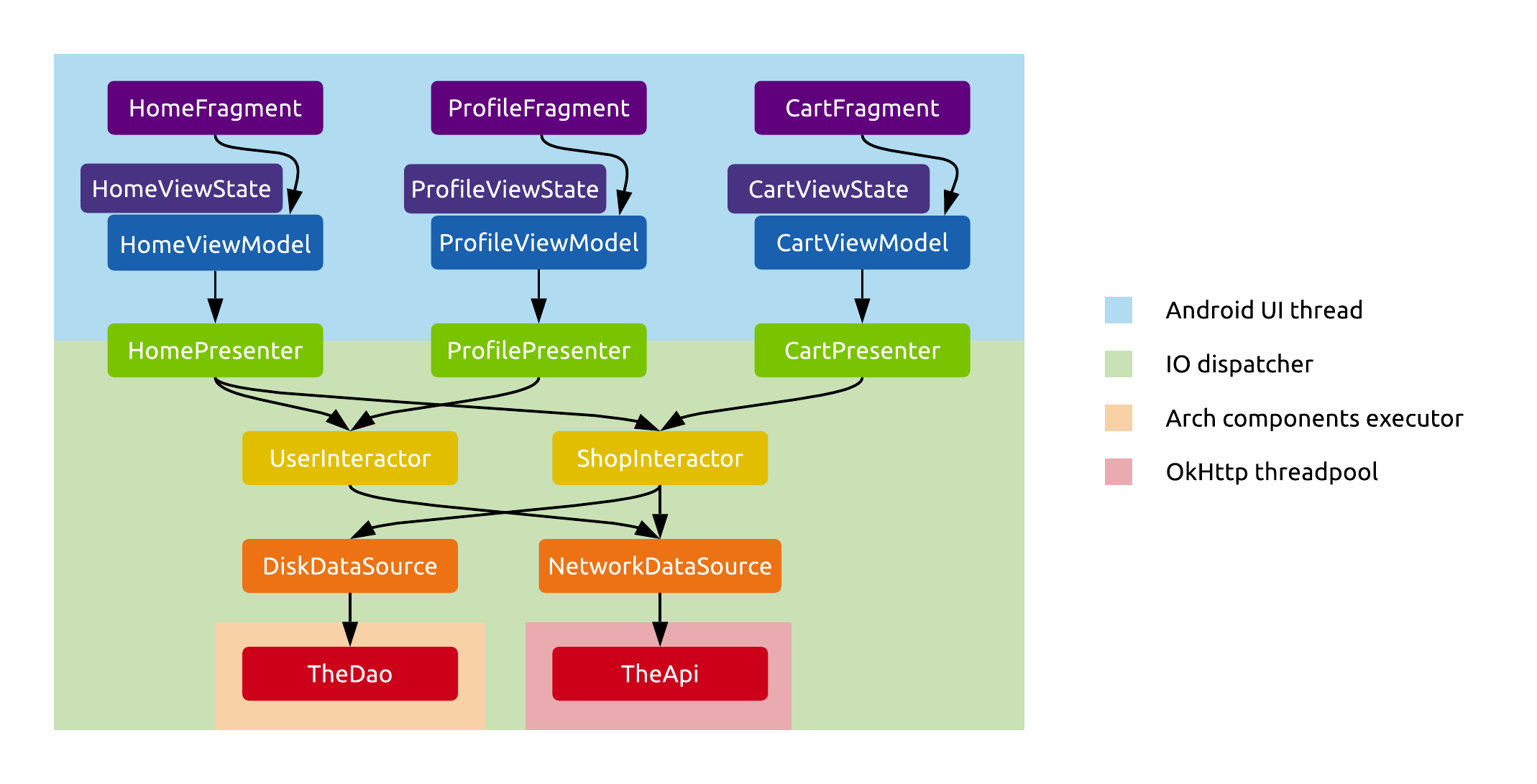

ViewModels start coroutines when Fragments call them. They start these on the UI dispatcher (i.e. on the UI thread), so that they can easily communicate state changes to the UI.

As soon as calls hit the Presenter layer, they’ll be moved to the IO dispatcher, and everything below this point runs on a background threadpool. This means that in the lower layers we may perform blocking calls freely, because they’ll just block one of these background threads.

One approach may be to make all calls from the Presenter downwards blocking, and this is the easiest thing to do. Just write non-suspending functions in the Interactors and in the Data sources - this shouldn’t be hard, as most APIs are blocking by default. If you do this, you’ll only be using coroutines to easily hop between the UI and IO threads.

However, you can also propagate the suspending nature of these calls down into the lower layers. You just need to mark the functions along the way with the suspend keyword, through the Interactors, and in the Data sources. If you do this, the lower layers will be aware that they are running inside coroutines. What are the benefits of this?

- You can support cancellation better. If all calls are blocking in the lower layers, cancelling the coroutine only cuts off execution when your calls return to the suspending parts of your code, the continuous blocking parts will always be executed together.

- You’re free to easily switch the thread your code is executing on. For example, you might have a data source which wants to have its own single thread wrapped in a

CoroutineContext. If its interface has all suspending functions, it can move all calls it receives to that single thread very easily with awithContextcall at the start of each of its public methods. - You might use advanced coroutine features in lower layers to implement either business logic or data sources.

In general, we probably want to make all of our Interactor methods suspending if there’s at least one Data source in the application that supports coroutines. This way, blocking data sources can block whatever background thread the call is currently on, and suspending data sources can move computations to their own dispatchers if and as they need to.

Note that a network data source can easily provide a suspending API using Retrofit, and the same can be done with a local database using Room.

Need to provide reactive data from lower layers? Consider using Flows.